There’s a lot of investor interest around State Bank of India stock, and it’s been elevated for almost a year now,” said a senior analyst with a foreign brokerage, which recently concluded an investors’ meet in Singapore. Interestingly, the stock price of India’s largest bank has returned over 77 per cent gains in five years, while the rest are still in the red. But the shareholding of foreign investors is barely reflective of the price appreciation, which has marginally reduced to about 10 per cent in a year.

“The top-of-the-mind question for foreign investors is whether SBI can sustain this performance,” says the analyst. For a bank that has everything going its way – from size to asset quality, product mix and profitability – it’s hard to fathom why such doubts crop up. This is also cue for the government to view and reposition the bank differently.

For one, SBI’s financial parameters are at multi-year best and, hence, it is truly too big to fail or disappoint, given its balance sheet size at ₹56-lakh crore, including ₹30-lakh crore of advances. Second, if approached well, it could offer simple solutions to many issues faced by the government. After all, the government is the largest stakeholder and shareholder of SBI.

Picture perfect

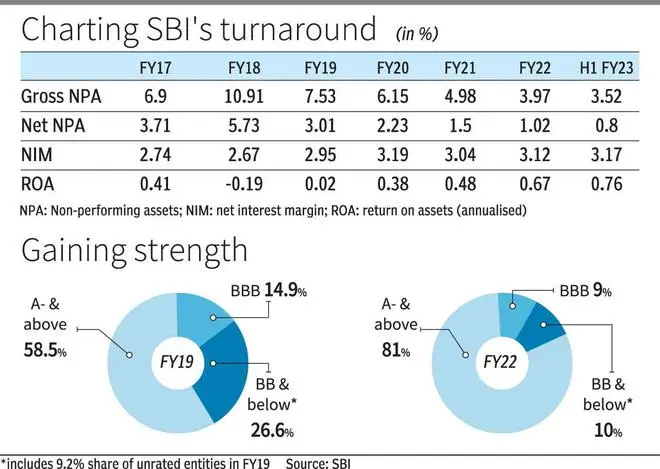

From FY18 to FY22, SBI has written off loans worth ₹1.9-lakh crore. Consequently, its gross non-performing assets reduced from 10.91 per cent to 3.97 per cent during this period. Alongside, the bank’s profitability and return ratios, too, have become better than before. What’s encouraging is the decline in slippages ratio, which was stubbornly over 2 per cent until FY20 to less than a per cent in recent times, indicating that the asset pool at SBI is a lot stable now.

The share of well-rated corporate loans have also shot up correspondingly and data points must instil confidence that SBI has certainly turned a new leaf. However, despite these quantitative improvements, if doubts persist, it’s probably because the past problems aren’t forgotten. The best way to remedy this to declutter from the old ways of functioning. In private sector entities, investors are clear that the objective of the business should be to maximise shareholders’ returns. In a state-owned outfit, that’s not the first motivating factor.

Invariably, given SBI’s size, scale, reach and the trust factor it has earned over the years, its often a vehicle at government’s disposal to launch its schemes, including its welfare efforts, and this is what is shooing away some of the large investors from SBI. Jan Dhan, MUDRA loans or Start-up India schemes are some examples.

While these are mass scale products, they don’t have a positive rub-off on the financials. The cost of failure of these projects are borne by the bank even if the idea didn’t germinate from within. This in fact is a systemic problem across PSU banks, but given SBI’s popularity among investors, the need to fix this issue has become critical. There’s yet another concern in people’s minds – how long will the asset quality improvement last? While Dinesh Khara, Chairman, SBI, has stated that “the only thing when we do underwriting is we should see that it should suit our appetite”, its pertinent to note that demand from corporates for loans is far from the peak levels of 2011-2014.

Once the appetite from India Inc vigorously rebounds, can SBI remain selective and not lower its guards on its risk management practices? “For SBI’s size, unless its some of the large big-ticket exposures turn bad, its unlikely that a repeat of 2017 will happen. But that’s again what sort of pull and push and cutting the corners happen while sanctioning a large loan,” said a former senior executive of SBI. The previous wave of boom in corporate loans has its nexus to the ‘courtesy’ calls from the North Block, and memories of these instances are still fresh.

“These practices aren’t so prevalent now, but we have to wait and see how the behaviour changes when the corporate credit cycle turns around,” said the former banker. With a Ministry of Finance representative at SBI’s board, its management – Chairman and four MDs – must remain focussed on their agenda, which will play a pivotal role in redefining investors’ interest in the bank.

At ₹5.35-lakh crore of market capitalisation, SBI is the most valuable state-owned company, with the government holding at 57.52 per cent. Government’s divestment target for FY22 stood at ₹65,000 crore. At times like these, when money is expensive and tough to come by, SBI could be a cash cow for the government if positioned carefully, given that dilution of even a per cent stake in the bank could fetch over ₹5,300 crore.

That’s a low-hanging fruit, which is currently least utilised from a divestment perspective. Turning to stronger names such as SBI would leave the government enough headroom to prepare for its ambitious bank privatisation agenda, and take it to the investors with the right narrative and at the right time.

Therefore, the question confronting SBI’s stakeholders is whether the bank should be an agent of its agenda or contribute meaningfully to its financials goals. Both cannot happen together and the time to take that call is now. This decision can go a long way in sustaining long-term investor interest and capital flows into SBI and India Inc.

Comments

Comments have to be in English, and in full sentences. They cannot be abusive or personal. Please abide by our community guidelines for posting your comments.

We have migrated to a new commenting platform. If you are already a registered user of TheHindu Businessline and logged in, you may continue to engage with our articles. If you do not have an account please register and login to post comments. Users can access their older comments by logging into their accounts on Vuukle.