While the global chip shortage has disrupted industries across the world, it has also prompted a surge in innovation aimed at addressing supply chain issues. In India, researchers and entrepreneurs have quickly responded to the shortage, providing critical innovations to improve the efficiency of the supply chain, tracking systems, diagnostics, and alternative materials.

As the chip shortage intensifies, however, it is critical for industries to remain at the forefront of global innovation to find long-term solutions. A three-pronged approach — imitate, innovate and protect — can promote innovation and facilitate patenting in India.

Imitate: Is one legally allowed to copy someone’s invention? The answer is yes, if the invention is not patented. A patent is a protected form of intellectual property to exclude others for a limited period of time from practising the invention within a territorial boundary — that is, the protection of rights is limited to the country in which the patent has been granted.

Many technologies that have been developed all over the world have not sought protection through patents in India. Therefore, one is free to take ideas and inventions from patents that have been granted outside the jurisdiction of India and implement or further develop them if they have not been patented in India.

Innovate: Though it is legal to imitate and copy certain innovations as discussed above, it may be more desirable to build on existing inventions with new innovations. However, what innovation is a patentable invention could differ significantly for different technologies.

In some areas like Computer Science (CS) or Information Technology (IT), patentable inventions do not necessarily require new experimental data. Patents in the field of CS or IT can be based on novel ideas, without actual reduction to practice, so long as the ideas can be practised without undue experiments. On the other hand, biotech and chemical patents on novel molecules require that molecules are synthesised, and that experimental data demonstrate reduction to practice.

However, even in the area of drug discovery, experimentation can be substantially reduced if predictive tools using artificial intelligence and biology can predict which drugs are likely to work and for which diseases.

China’s strategy

Protect: Once the innovation occurs, the immediate next step is to protect that innovation through patents before disclosing, using or selling the product of the invention. Indeed, China employed this strategy in the early 2000s, when they began to imitate, innovate and protect innovations based on foundational ideas obtained from all around the world.

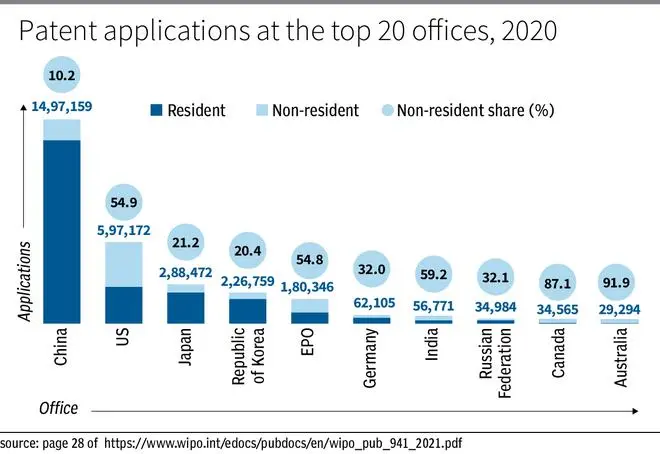

This strategy propelled China to be No. 1 in patent applications filed in 2020 by a huge margin over the US (2) and India (9) — 1,497,159 versus 597,172 and 56,771 in the US and India, respectively (see chart) .

The domestic applications filed in China, the US and India in 2020, based on percentage of domestic filings, are 10.2 per cent, 54.9 per cent and 59.2 per cent, respectively.

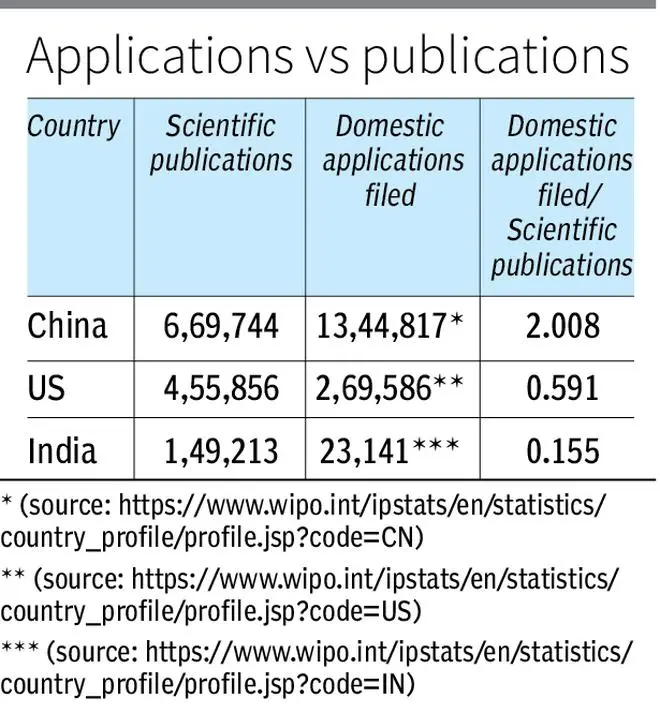

Now, let’s look at the number of scientific articles published from China, the US and India. During 2020, China published 669,744 scientific articles, the US 455,856, and India came third with 149,213.

The Table shows the ratio of number of domestic patent applications filed and the number of scientific publications in 2020 in China, US and India.

In short, India is doing very well in scientific publications — it’s third in the world. Yet, when it comes to domestic patent application filings, the number is low in proportion to the number of scientific publications.

The time is ripe for India to focus on patenting in addition to publishing scientific articles.

Patenting often leads to licensing and cross-licensing of the patents. An example of patenting and cross-licensing is provided here for better understanding. Suppose person A has invented a pencil and person B after replicating the idea of pencil, came up with the idea of adding an eraser onto the pencil. Person B’s innovation is the addition of the eraser to the pencil, and can be granted a patent assuming that a pencil with an eraser is novel and inventive over the pencil, which is considered prior art.

The following two scenarios use this example to illustrate important nuances of a patented innovation, which ultimately could allow persons A and B to sell products on the market.

Person A who invented the pencil doesn’t file a patent for pencil: In this case, person B is absolutely free to manufacture and sell the product of pencil with eraser, as the pencil itself has not been patented.

Further, any other person can make pencils and sell them as they are known prior to the invention of pencil with eraser, but they do not have rights to make, use, sell, or import the patented pencil with eraser in the jurisdictions where person B’s invention is protected without the permission from person B.

Person A who invented the pencil files a patent for pencil: In this scenario, as soon as person B makes or uses the pencil to put the eraser on the pencil, she will be infringing the patent of person A, assuming that person A’s patent is granted and unexpired. This is because for person B to make a pencil plus eraser, she has to first make or use the patented pencil.

Indeed, person B cannot practice her own invention without licensing the patent on the pencil from person A.

Vice-versa, person A cannot make or sell a pencil with an eraser without a licence from person B. Assume that the market demand is for a pencil plus eraser.

Yet, neither person A nor person B can make it. So, one scenario is for persons A and B to cross licence their patents to each other, thereby permitting both persons A and B to make and sell a pencil plus eraser, but maybe in different territories.

In the context of chip shortage-related innovations, here are some strategies that Indian tech companies could adopt: (a) they should look to chip designs and technologies for which no patent applications have been filed in India; (b) for existing chip patents filed in India, they should employ chip development tools to further innovate new ways to repurpose these designs; and (c) they can enter into a licensing agreement with foreign companies to affordably manufacture and sell the new chip designs.

The writer is President, Davé Law Group, and Visiting Professor at Gujarat National Law University, Gandhinagar

Comments

Comments have to be in English, and in full sentences. They cannot be abusive or personal. Please abide by our community guidelines for posting your comments.

We have migrated to a new commenting platform. If you are already a registered user of TheHindu Businessline and logged in, you may continue to engage with our articles. If you do not have an account please register and login to post comments. Users can access their older comments by logging into their accounts on Vuukle.