On July 1, 2017, the Goods and Services Tax (GST) law was introduced and there began a new chapter in the history of indirect taxation and we are celebrating its sixth anniversary this year.

GST was aimed at resolving issues created by multiplicity of indirect taxes, resulting in a complex tax structure, high incidence of taxes and loss of tax credits in supply chain. This was creating issues like higher compliance cost, uneven tax rates, broken tax credit chain and unfair competition due to geographical location. Thus GST, a unified tax structure, was created, which is legislated and administered concurrently by the Central and State governments.

Under earlier tax regimes, the credit of many taxes/levies paid by the suppliers was not available to them and this was not only increasing the final cost but was also blocking the working capital. However, this issue has been addressed by the introduction of Input Tax Credit (ITC). Moreover, refund of GST paid on export of goods is now fully automated, whereby the shipping bill filed by the exporter is also treated as an application and the refund is directly credited to exporter’s bank account.

The most important aspect of GST was introduction of an uniform and unbroken chain of ITC. This effectively reduces tax liability to the extent of taxes paid on purchases and results in taxation of only value addition by the supplier, thereby avoiding cascading effect of tax on supplies.

This results in substantial tax savings and helps in reducing the requirement of working capital, ranging from 5 per cent to 28 per cent — depending on inputs and input services procured. Besides, there are also provisions for cash refund of ITC in two situations, where the tax on output cannot be set-off against the taxes on input. This is when the former is zero rated or the tax is less than the input tax. Exports/supplies to SEZs are zero rated. The accumulated tax credit in such cases is refunded into the bank account of the producer.

Such tax-credits add to short-term assets of a business entity, which in turn helps to meet short-term liabilities. This is important because when short-term assets are insufficient to meet short-term liabilities, then enterprises are forced to sell long-term assets (like land, machinery, etc.) to meet short-term liabilities, eventually leading to insolvency.

Thus, tax-credits under GST and benefits under the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC), 2016 are complementary to each other, as both augment ease of entry and exit of firms in a market economy. However, businesses also need to be aware of the restrictions in the ITC scheme — that is, the goods or services and the situations, where ITC is not allowed.

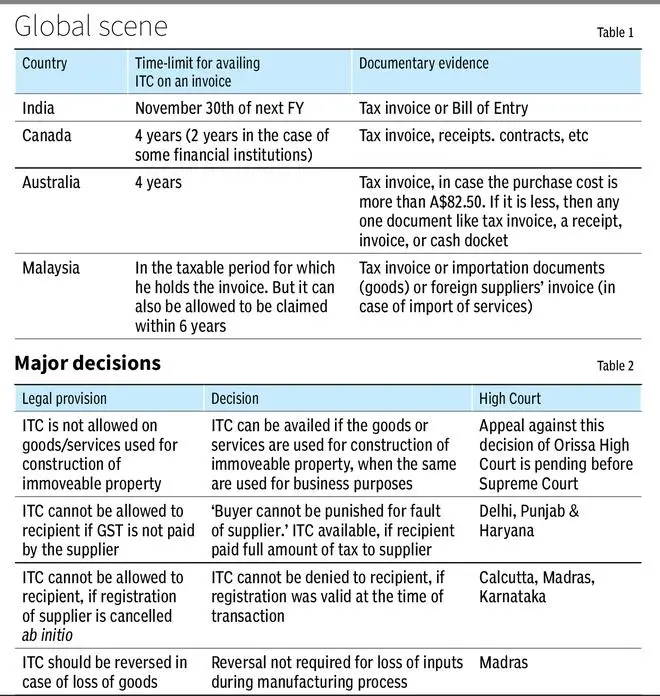

The GST or VAT system is being followed in 175 countries, after its first introduction in France in 1954. The basic tenet of VAT or GST, across the globe, is taxation of only value addition, therefore, all these countries follow the ITC mechanism. Though the basic concept is same, there are some variations in procedures or restrictions under the laws of different countries (see Table 1).

Issues and concerns

In comparison to legal provisions under a similar scheme in the Central Excise Act, the legal provisions under GST law are more intricate. Like any other beneficial scheme, the ITC is also subject to certain conditions — example, supplier must have deposited the tax with government, claim must be made within specified time-limit, goods/services should have been received along with invoice, etc.

Besides, ITC is not allowed on some goods or services, even though the same are used for business purposes — example, motor vehicles, goods/services used for immoveable property, etc. These issues have raised many concerns and contested between the government and taxpayers. Some major decisions on the same are presented in Table 2.

As the GST regime enters its seventh year of implementation, the law is continuously evolving to acquire a robust structure to address the issues faced by taxpayers, while increasing the beneficial provisions for the trade. It is, therefore, important for Indian businesses to keep an eye on new amendments to the GST law and leverage various benefits, to become globally competitive and market leaders in their field of activity.

Dhananjay is a Civil Servant in the Government of India, and Sengar is a retired IRS officer. Views are personal

Comments

Comments have to be in English, and in full sentences. They cannot be abusive or personal. Please abide by our community guidelines for posting your comments.

We have migrated to a new commenting platform. If you are already a registered user of TheHindu Businessline and logged in, you may continue to engage with our articles. If you do not have an account please register and login to post comments. Users can access their older comments by logging into their accounts on Vuukle.