The 8.7 per cent growth in GDP for 2021-22 may be one of the fastest rates in the world but in absolute terms it only restores the economy back to 2019-20 levels. This may also suggest resilience especially if we look at how individual components moved in a supply (GVA) and demand (GDP) format

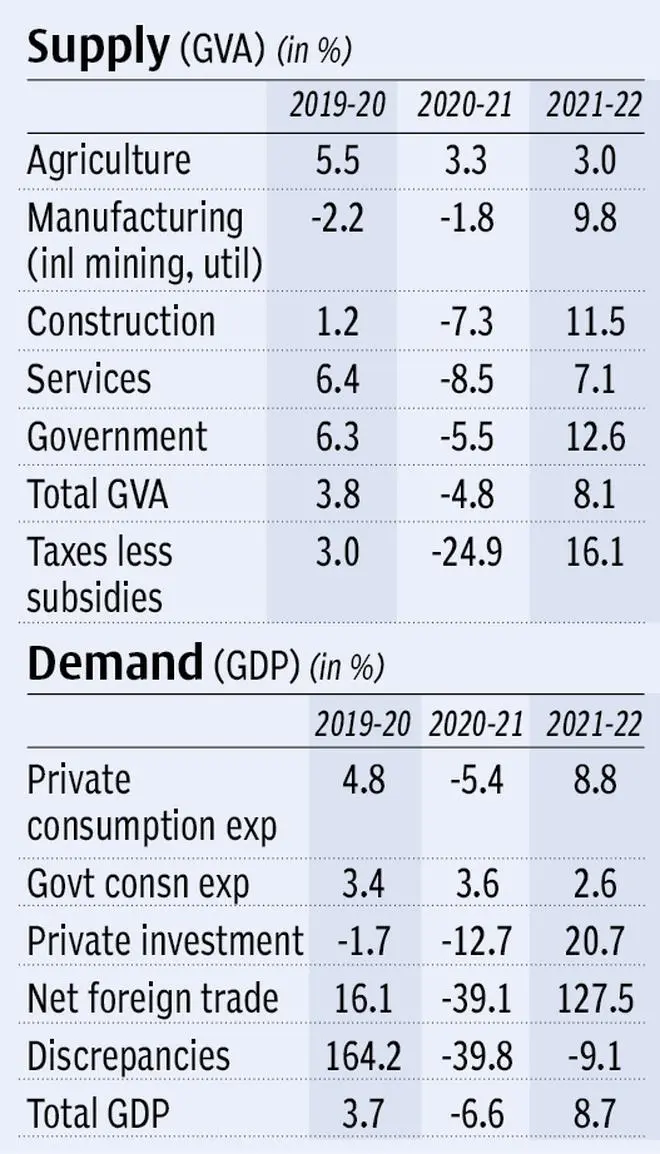

The contraction in supply during 2020-21 was across the board (except agriculture) and quite obviously due to constraints imposed by the pandemic, war and even climate. The recovery in 2021-22 reflects the easing of some of them, besides of course the low-base effects.

On the demand (GDP) side, the fall looked more likely due to contraction in economic activity in 2020-21 than any long-term decline in incomes, which is also supported by the fact that recovery came with the revival of economic activity.

This is clearer when we look at the individual components of demand. The 5.4 per cent decline in private consumption, the largest driver of growth, was due to declines in spending on personal transport (-14 per cent) and transport services (-24 per cent) rather than food, which is the biggest item of consumption. In fact, spending on food went up (4 per cent) despite declining incomes, in no small measure due to government relief measures as well.

Services demand also declined (-9 per cent) reflecting the overall contraction in economic activity, especially in the so-called ‘non-contactless’ sectors.

As for the other major driver, private investment, it was in decline even before the pandemic and continued to fall (-12.7 per cent). Net foreign trade has always impacted GDP disproportionately to its share, due to the fact that trade deficits are subtracted from GDP.

Thus, the large fall in deficit during 2020-21 (-39.1 per cent) helped soften the decline in GDP. But strikingly, as things eased up in 2021-22, imports led by petroleum, jumped 35 per cent causing net trade deficit to rise by a whopping 127.5 per cent. Finally, net taxes to government also fell sharply (-24.9 per cent) in 2020-21, pulling GDP down more sharply than GVA, since taxes separate the two (see table).

There is a common link in all these components viz. energy, specifically petroleum, which now has an all-pervasive influence. For one, petroleum and energy-based items now account for about 18 per cent of private consumption spending (growing at an average 10 per cent prior to the pandemic) and the sudden drop of 16 per cent during 2020-21 dented GDP. Next, petroleum contributes almost a fifth of all indirect taxes (Centre and States together) and indirect taxes are about 50 per cent of all tax revenues.

This is a significant dependence which explains the huge fall in taxes (-24.9 per cent). A third aspect is that petroleum imports, on average, are about 85 per cent of trade deficit and the impact that deficits have on GDP, inflation and external value of the rupee is well-known.

Finally, the petroleum link to inflation is unmistakable. It was earlier understated in core inflation calculations because of the structuring of weights (fuel and light did not include petrol and diesel but were under transportation services).

But the fact that modified core inflation (introduced since June 2020, excluding all fuels) has been running lower than conventional core inflation shows the impact of fuel prices.

Chain effect

The energy intensity of the economy is not its only problem. The low-income trap (per capita income under $2,000) is itself the result of several legacy structural deficiencies — informal economy, low labour force participation, low literacy and low productivity. Low incomes create a chain of impact.

It restricts the consumption and demand base needed for growth, but importantly narrows the tax base, which is crucial for financing government intervention in the economy, necessitated in the first place by low income and high inequality.

This has led to a significantly high dependence on indirect taxes (49 per cent), which is not only regressive but also unsustainable in the long run. This sets in motion another chain of effects that we have seen at work — fall in consumption leading to fall in taxes, increase in borrowings and inflationary pressures.

The import intensity of energy adds to the woes — persistent trade deficits require higher levels of foreign exchange reserves, which are now increasingly dependent on capital flows (FDI, portfolio investment) than trade and whose impact on inflation and exchange rates cannot be ignored.

The recovery in growth is akin to the economic machine restarting after power is restored to it and cannot be construed as the beginning of a new growth story. The question is not about being the fastest growing economy but about the rate that would propel it out of its low-income orbit and its attendant problems.

The writer is an independent financial consultant

Comments

Comments have to be in English, and in full sentences. They cannot be abusive or personal. Please abide by our community guidelines for posting your comments.

We have migrated to a new commenting platform. If you are already a registered user of TheHindu Businessline and logged in, you may continue to engage with our articles. If you do not have an account please register and login to post comments. Users can access their older comments by logging into their accounts on Vuukle.