There has been a dramatic turnaround in gross non-performing assets (GNPA) ratio of Indian banks. In 2017-18, this ratio was as high as 11.2 per cent raising concerns on the stability of the banking system. But this ratio has come down to 3.9 per cent bringing cheer to policymakers and bankers. How does one explain this transformation? The purpose of this article is to look at the data and offer an explanation and also point out some concerns in the midst of satisfaction.

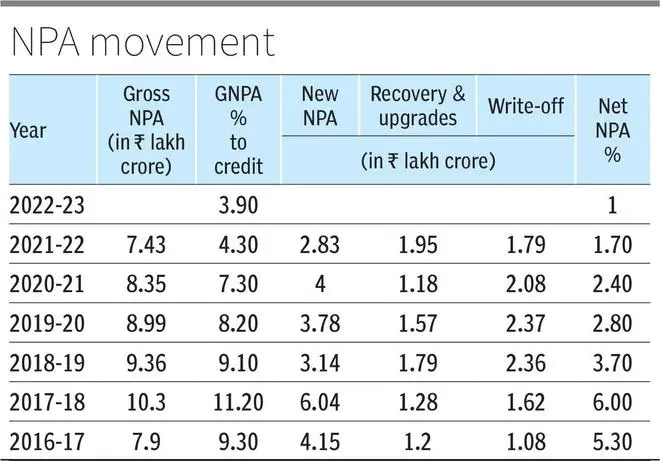

The Table provides data on the movement of NPAs between 2016-17 and 2021-22. For 2022-23, only data on the overall ratio is available. The major highlights that emerge from the Table are:

After reaching a peak of ₹10.3-lakh crore in 2017-18, GNPA came down to ₹7.4-lakh crore in 2021-22. GNPA as a percentage of credit came down from 11.2 per cent in 2017-18 to 4.3 per cent in 2021-22. It has subsequently come down to 3.9 per cent in 2022-23. But full data for that year are not available.

There has been a substantial write-off of NPAs by banks year after year. The total write-off since 2016-17 amount to around ₹10-lakh crore.

There have been fresh NPAs. They add up to ₹10.61-lakh core during the last three years (2019-22) alone.

Is write-off a worry?

Should large write-offs cause concern? Not necessarily. All banks do this in order to clean up balance sheets and provide a good picture of the banks. Some recent data show that private banks have been more active in writing off NPAs than public sector banks (PSBs) . In fact, the write-off is possible only if banks earn adequate profits. During 2022-23 PSBs earned an aggregate profit of nearly ₹1-lakh crore. This is on the back of ₹66,453 crore during the previous year.

Other performance metrics like ROA (return on assets), ROE (return on equity) and NIM (net interest margin) have significantly improved. Thus, writing off per se should not be a source of worry. It may in one sense reflect the strength of banks to undertake write-off. But what is a matter of concern is lack of adequate recoveries.

The Finance Minister informed Parliament on December 19, 2022, that over the last five years banks have written off around ₹10-lakh crore and cleaned the balance sheets. They recovered around ₹6.5-lakh crore including ₹1.32-lakh crore out of the written-off accounts. Recoveries as percentage of write-off amount to only 13 per cent. One would have liked more recoveries.

The data we have put together also suggest that there have been new NPAs. Some of that may have come out of previous loans and not necessarily from new loans. A redefinition of what constitutes NPA may also lead to new NPAs out of old loans.

The reduction in ratio may also happen because the denominator (total credit) may be growing at a faster rate. Unless the new loans are assessed properly, it may cause NPAs to go up again.

The reduction in NPA ratio is a good sign. The banking system needs to be congratulated on this. But we should not be complacent and drop the guard. But the low recoveries out of write-off loans compel us to take a relook at our credit assessment, disbursal and monitoring procedures so that the banking system does not in the first place accumulate excessive NPAs. This leads us to the question of how to prevent accumulation of NPAs which we had addressed earlier (see businessline dated August 3 and 4, 2021). Some major issues are highlighted below.

Preventing NPA accumulation

Firstly, banks need to revisit their business models as fault-lines would lead to higher NPAs and credit losses. The credit portfolios of banks are quite diversified from small ticket gold loans/ unsecured personal loans/ loans to hawkers to complex, high risk and big-ticket infrastructure loans. Ideally, from lending perspective, banks need as many business models as credit segments and customer segments.

A typical business model has building blocks like value proposition, customer segments, customer acquisition and relations, delivery channels on one hand and key activities, key resources and key partnerships on the other. All these vary from credit product to product and risk profile to risk profile. Banks need to tightly but dynamically align various building blocks to mitigate NPAs and credit losses.

Secondly, there has been lot of emphasis on board/corporate governance and this is a usual suspect behind the pile up of NPAs and even bank failures. But other layers of governance like business, risk and operational governance are equally if not more important to mitigate NPAs. The seeds of mis-governance/NPAs are sown in these layers. Lenders may need to revisit these layers and even subject them to an assurance audit at least yearly.

Thirdly, there is need to fine tune risk appetite. Though it needs to be in measurable terms, it is not just one raw number. It needs to be aligned to risk culture, underwriting skills in a particular domain, risk tolerance. Risk appetite cannot be uniform across all credit segments.

Fourthly, the diversion of funds in corporate lending is as old as banking. It looks as though the problem is more widespread and intense now. Bankers in consortium need to collaborate in good times so that these practices are detected early and remedied.

Fifthly, the quantum of NPA recoveries of around 25 per cent of the claim amount, through various channels, is far from satisfactory. Even under the IBC regime the recovery rate has fallen from over 45 per cent to about 23.8 per cent. The government, regulators and lenders need to rework these recovery/resolution frameworks so that massive haircuts (sometimes as high as 90 per cent) are cut drastically. These massive haircuts only end in huge write-offs as we are witnessing now.

Sixthly, banks need to develop a cadre of turnaround experts. Underwriting skills and turnaround skills are like chalk and cheese. This is important as the changes in industry and real economy are quite fast and global.

Seventhly, net zero commitment is having profound impact on industries. New credit risks lurk in the corner. The RBI/Government need to handhold lenders to navigate these unknown waters.

The regulations mandate banks to provide 100 per cent provision in accounts classified as fraud. Even if the diversion/siphoning off of funds is 5-10 per cent of the outstanding exposure, of say ₹10,000 crore, the entire amount needs to be provided and they are written off subsequently. This has also been contributing to the spike in new NPAs. The impact of these regulations on the haircuts needs to be examined.

The authors well recognise and acknowledge that zero NPA is neither feasible nor desirable. But credit costs need to be manageable. This needs new approaches, new tools, new models and revisiting all the layers of governance.

Lenders, regulators and the Government have their task cut out and need to be watchful of credit trends as our aspirations rise high. As the saying goes, “Bad loans are sown in good times.”

Rangarajan is former Chairman, Economic Advisory Council to the Prime Minister, and Sambamurthy is former Director and CEO, IDRBT

Comments

Comments have to be in English, and in full sentences. They cannot be abusive or personal. Please abide by our community guidelines for posting your comments.

We have migrated to a new commenting platform. If you are already a registered user of TheHindu Businessline and logged in, you may continue to engage with our articles. If you do not have an account please register and login to post comments. Users can access their older comments by logging into their accounts on Vuukle.