Indian society is extremely complex. While the intellectual capability to compete with other economies in almost every field is irrefutable, the social and cultural underpinnings tend to impede progress in many areas. Women’s participation in work force is one such instance.

What set the alarm bells ringing was the World Economic Forum’s gender gap report 2022, where India was ranked at 135th position out of 146 countries. The rank in economic participation and opportunity was particularly abysmal with India at 143rd position. This poor performance is largely due to a very low participation of Indian women in the work force.

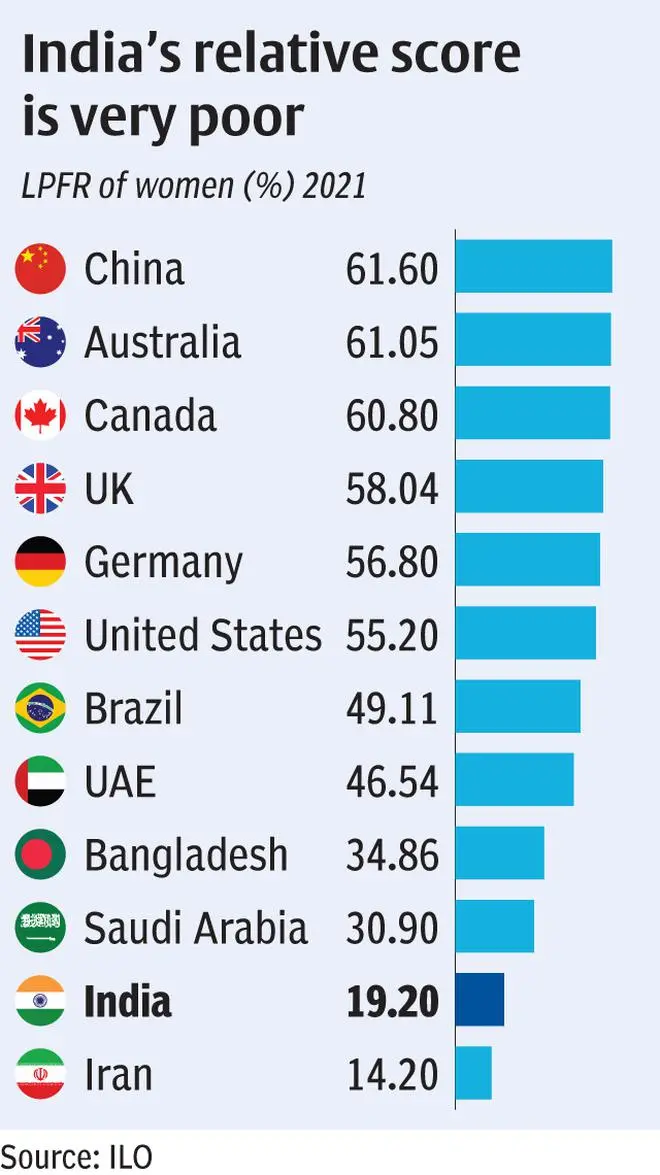

From 30.7 per cent in 2006, the proportion of working age women taking part in paid work dropped to 19.2 per cent in 2021, according to the World Bank. While the pandemic could be partly responsible for severe job losses among women, the percentage of employed women has been quite low over the past decade, averaging 21 per cent between 2012 and 2021.

Also, India fares much worse than most countries on this score. While 46 per cent of the women were part of the workforce on an average globally in 2021, the numbers were much higher in many countries. China, for instance, had 61 per cent of its women in workforce while the US had 55 per cent.

Something is clearly not right. Why are women dropping out of labour force?

The reasons behind the dip

According to ILO, “Based on global evidence, some of the most important drivers (for lower participation of women in workforce) include educational attainment, fertility rates and the age of marriage, economic growth/cyclical effects, and urbanisation. In addition to these issues, social norms determining the role of women in the public domain continue to affect outcomes.”

There are many reasons, unique to India, which could account for the drop in recent years.

One, literacy levels among women has been improving over the last few decades. With women aged above 15 (parameter considered by the World Bank) increasingly enrolling for higher studies in colleges, their participation in workforce could have dropped.

Two, the rising income, especially among the urban population could have removed the economic incentive for women to work. The difficulties in commuting to work in cities bolster such decisions.

Three, the country has not created enough jobs and the demand-supply gap in employment opportunities results in women deciding to stay at home. Four, most Indian women are deeply engaged in running households, which is unpaid work, and does not count as being part of workforce.

There is no doubt that the loss to the economy due to this large army of workforce staying away, is huge. An IMF blog by Christine Lagarde and Jonathan D Ostry estimates that closing the gender gap for countries ranking in the lower half in gender inequality could increase GDP by an average of 35 per cent.

“Four fifths of these gains come from adding workers to the labour force, but fully one fifth of the gains are due to the gender diversity effect on productivity.”

Women friendly WFH jobs

One of the main reasons urban Indian women drop out of work after marriage is due to the difficulty in balancing household responsibilities and paid-work outside, which typically requires being away from home through the day and often involves arduous commutes. Labour force participation is higher among rural women in India because they can easily get work closer to home and for limited hours.

However, many women are willing to work if it is available in their premises and has flexible hours. ILO finds that 34 per cent of rural Indian women and 28 per cent of urban women are willing to accept work at home. More than 90 per cent of the women willing to work want work on a regular basis and over 70 per cent of them preferred ‘part-time’ work on a regular basis.

The pandemic has shown us the solution to this problem -- work-from-home. This model needs to be used to provide work to women who have dropped out of the workforce. The government can take a lead here by creating jobs especially for women which can be done in windows of 3 or 4 hours every day from home. Some basic skill-training may be required, cost of which has to be borne by the government.

Tax breaks

Corporate India has not really been very welcoming of women. Only around a quarter of India Inc’s employees are women. The proportion is lower in start-ups which have just 20 per cent employees as women.

Not only are fewer women employed by companies, they are also paid lower salaries for the same kind of work compared to men and their average income is also lower, according to the WEF gender gap report.

Companies need to be nudged to correct this imbalance. This can be done by offering a tax incentive, say 2 per cent lower corporate tax rate, for companies in which at least 50 per cent of workforce is made up of women. Tax incentive can be higher for companies following other gender equity practices such as equal opportunities and uniform pay-scales.

Ease onerous laws

Many of the laws made by the government to support women in fact work against them. Employers may be wary of employing younger women who may avail of 26 weeks of paid maternity leave and require the company to set up a creche for their children, as laid down in the Maternity Benefit Act.

It is good that women are given longer time to recover after delivering a child and are allowed time to take care of their infants at a critical period, but asking companies to bear the entire burden of paid leave is not fair. In many countries, the social security benefits given by the government cover the payments during maternity leave, partially or completely. If the government steps up to compensate companies for their payouts during maternity leave, more companies may come forward to employ women. Else, companies can be allowed weighted tax deduction for salaries given during maternity leave.

Similarly, The State of Discrimination Report by Trayas Foundation reports that “as on date, more than 50 Acts and 150 Rules across Indian states prevent women from choosing to work. Women in India cannot work at night (after 6 PM), or in jobs deemed arduous (underground mines, lifting heavy objects), hazardous (in at least 27 factory processes), and morally inappropriate (jobs involving sale of liquor).”

There is a need to review these laws to provide more freedom to women to choose work.

Comments

Comments have to be in English, and in full sentences. They cannot be abusive or personal. Please abide by our community guidelines for posting your comments.

We have migrated to a new commenting platform. If you are already a registered user of TheHindu Businessline and logged in, you may continue to engage with our articles. If you do not have an account please register and login to post comments. Users can access their older comments by logging into their accounts on Vuukle.