The US Fed has begun unwinding its easy monetary policy and markets have begun rolling on the floor starting taper tantrum 2.0. Riskier assets where most of the speculative money had been parked over the last two years are witnessing large meltdowns.

The Nasdaq composite index has declined over 9 per cent since the Fed meeting last week in which the fed funds rate was hiked by 50 basis point; for the second time this year. It has also announced monthly reduction of outstanding bonds beginning this June.

Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies are witnessing a virtual stampede towards the exit door with prices down over 15 per cent in the last one week. 10-year US sovereign bond yields crossed 3 per cent, dollar index shot up and there is run on emerging market currencies and bonds.

We cannot really blame the markets for trying to arm-twist the Fed, for the taper tantrum 1.0 in 2019 had been quite effective.

The sell-off in equity and bond market in the last quarter of 2019 had made the Fed halt its rate hike and balance sheet contraction, despite the economy being on a sound footing.

Will the Fed stay the course this time, unlike in 2019? It is highly likely that the Fed will be unmoved by markets’ shenanigans this time. One, US President Joe Biden is unlikely to get worked up about stock market crash and influence the Fed to backtrack, the way Donald Trump did. Two, the US debt pile up has grown too high for Fed to take it easy any more.

No Trump effect

Donald Trump was a great follower of the market ticker and believed that the Bull-run in the Dow Jones during his tenure was a testimony of the effectiveness of his Presidency. He also believed that interest rates need to be lowered and not hiked to help stock markets. He exerted enormous pressure on the Federal Reserve in 2018 and 2019 through acerbic tweets to roll back monetary tightening.

According to an analysis by Yahoo Finance, he tweeted 100 times about the Fed since the appointment of Jerome Powell as the Chairman and these tweets increased in the days preceding the policy meeting.

“The only problem our economy has is the Fed. They don’t have a feel for the Market…,” went one tweet in December 2018.

“It would be sooo great if the Fed would further lower interest rates and quantitative ease. The Dollar is very strong against other currencies and there is almost no inflation. This is the time to do it. Exports would zoom,” ran one of his other tweets in December 2019.

Jerome Powell is surely a happier man now, since he can carry on with his task without a belligerent POTUS breathing down his neck. In a big relief to Powell, Joe Biden has not shown any great interest in stock or other markets so far.

The other reason why the Fed is unlikely to backtrack is because the large debt pile it has built since 2008.

The growing debt pile

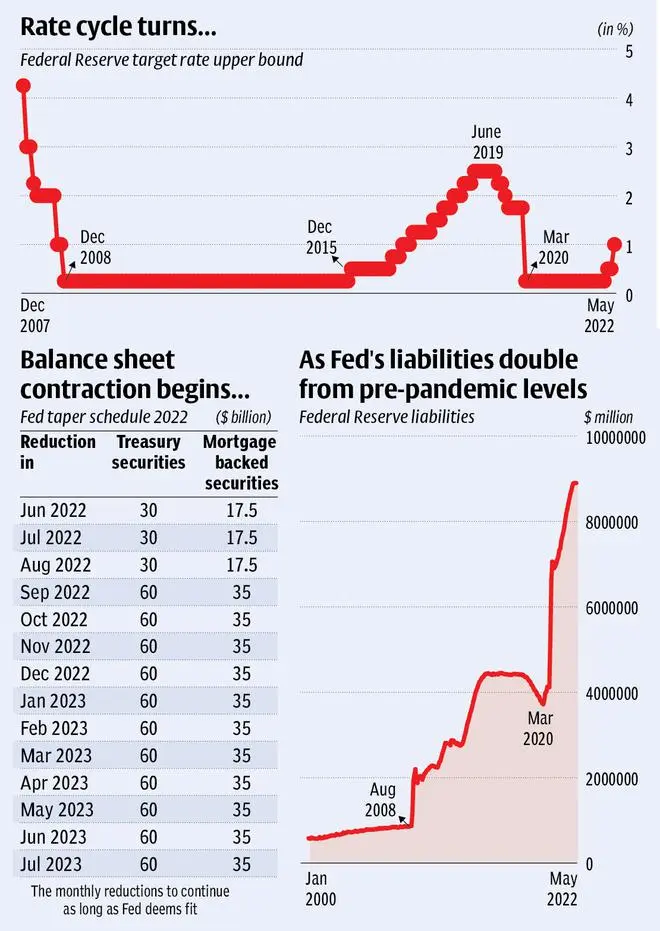

The liabilities of the Federal Reserve were at $869 billion in August 2008. As the central bank began printing money from the last quarter of 2008, liabilities grew steadily to stand at $4,427 billion by the end of December 2015.

While addition of fresh liabilities ceased in 2015, the Fed could reduce outstanding liabilities only much later, between October 2017 and September 2019. But then, the balance sheet contraction was halted and fresh stimulus program began in 2019, at Trump’s prompting, “to save the flailing markets”.

Due to Powell’s inability to tighten under Trump, Fed’s liabilities were an elevated $4,120 billion in February 2020. The pandemic related stimulus has added another $4,778 billion with total liabilities now standing at $8,898 billion.

This level of debt is clearly untenable. Fed’s liabilities as percentage of US GDP was 6 per cent prior to 2008. It rose to 19.2 per cent in February 2020 and stood at 37.5 per cent in April 2022. Research has shown that consequences of high public debt are high inflation and slowing growth; these are already manifesting themselves in the US economy. If these persist, the country could head towards stagflation.

High government borrowing also crowds out private investment, impacts long-term output of the economy and could lead to unfavourable fiscal measures to finance the debt burden.

Lessons from taper 1.0

The Fed Chairman Jerome Powell is therefore in a hurry to reduce this debt burden. He also seems to have learnt from the mistakes made in taper schedule between 2015-19. The Fed had waited for too long, almost seven years, after the GFC to begin winding down the stimulus. It had also proceeded extremely slowly and cautiously, making one 25 bps hike in December 2015, next 25 bps hike in December 2016 followed by seven more hikes until late 2018, after which it stopped hiking rates.

The balance sheet contraction was also extremely slow with just $10 billion of securities being retired every month from October 2017, to be hiked gradually to $50 billion per month by October 2018.

The Fed however appears determined to speed up the interest rate hikes as well as balance sheet contraction this time (see table). About $95 billion of treasury and mortgage backed securities will be retired every month from this September. But even at this level, it will be 2026 by the time Fed’s liabilities reach pre-pandemic levels. Interest rate hikes are also being front-loaded so that another adverse event does not stall policy normalisation. FOMC members’ median projections point towards another 90 bps hikes in 2022 and 100 bps hike in 2023.

Can markets bear this?

Given that the monetary policy normalisation is expected to continue over many years, market participants may eventually have to adjust to an era of lower liquidity and accept that it is alright for asset prices to move lower to their fair value.

India is going to be impacted by the rising cost of overseas borrowings for Indian companies and government. Foreign portfolio flows may continue for some more time from Indian equities and bonds thus applying pressure on the rupee too. But once global markets settle down to the new norm of lower liquidity and higher rates, Indian markets will also follow.

Comments

Comments have to be in English, and in full sentences. They cannot be abusive or personal. Please abide by our community guidelines for posting your comments.

We have migrated to a new commenting platform. If you are already a registered user of TheHindu Businessline and logged in, you may continue to engage with our articles. If you do not have an account please register and login to post comments. Users can access their older comments by logging into their accounts on Vuukle.